Gen Con Vs. Discrimination

/

“The legislation, SB 101, is about respecting and reassuring Hoosiers that their religious freedoms are intact. I strongly support the legislation and applaud the members of the General Assembly for their work on this important issue. I look forward to signing the bill when it reaches my desk.”

- Indiana Governor Mike Pence ( R )

There are a handful of things which help to define my character. I am a father, a husband, a writer, a bisexual man, and I am a gamer. If you have anything more than a passing acquaintance with my work I’m sure this does not come as a surprise but it needs to be repeated before we dive head first into the pool without looking to see if it’s filled with water, worms, or broken glass.

I’m Josh, that’s how I roll.

Looked at objectively things are bright for the LGBT community in terms of our future in America. Alost all states have marriage equality, it’s looking as if the Supreme court will be making it the law of the land in June (go fuck yourself Scalia), and community after community have passed laws protecting the Civil Rights of their LGBT citizens.

Grand Rapids, have I told you lately I love you so hard?

Of course there are dark spots. Roy Moore is playing a second rate McGovern down in Alabama, the Duggar cult made sure Fayetteville remained a place where it was safe to be a queer beater and chaser, and the Hoosier state is determined to finish the job Jan Brewer (former Governor of Arizona) wussed out on. As of this writing Mike Pence, the Hoosier Governor, is practically coming in his khakis to sign the “Religious Freedom Bill” (SB101) into law.

Indiana House passes controversial religious freedom bill

By Sarah Pulliam Bailey March 23

Indiana Gov. Mike Pence speaks at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) on Feb. 27 in National Harbor, Md. Pence is expected to sign a controversial bill into law that would allow business owners to decline to provide services for same-sex couples. (Alex Brandon/AP)

A controversial religious freedom bill that would protect business owners who want to decline to provide services for same-sex couples was passed by Indiana’s State House today, the latest in a larger battle over same-sex marriage and rights.

The bill reflects a national debate over the dividing line between religious liberty and anti-gay discrimination. The question of whether the religious rights of business owners also extend to their for-profit companies has been a flashpoint as part of a larger debate over same-sex marriage. For instance, the bill would protect a wedding photographer who objects to shooting a same-sex wedding.

Religious Freedom Restoration Act opponents prepare to deliver about 10,000 letters stacked in two red wagons to the office of Indiana House of Representatives Speaker Brian Bosma, R-Indianapolis, at the Indiana Statehouse in Indianapolis on Monday, March 23, 2015. Supporters say the legislation would protect religious freedoms, but opponents say it would allow discrimination against gays and lesbians. (AP Photo/The Indianapolis Star, Charlie Nye)

The Indiana House voted 63 to 31 to approve a hot-button bill that will likely become law, and Republican Gov. Mike Pence said he plans to sign the legislation when it lands on his desk. The state Senate’s version of the bill would prevent the government from “substantially burdening” a person’s exercise of religion unless the government can prove it has a compelling interest and is doing so in the least restrictive means.

Supporters say the measure supports religious freedom while opponents fear discrimination against LGBT people. The push towards this kind of legislation comes as same-sex marriage becomes legal across the country. In September, a federal court ruling struck down bans on same-sex marriage in Indiana and other states.

Jason Collins, an athlete who publicly came out as gay after the 2013 NBA season, will be in Indianapolis as a Yahoo Sports analyst covering the NCAA Final Four and publicly questioned the bill.

Indiana’s religious freedom bill is modeled on a 22-year-old federal law called the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act, which played a key role in the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision in 2014. The court ruled that closely held corporations with religious objections do not have to comply with health-care requirements that they cover contraceptives like Plan B.

A growing list of cities are passing gay anti-discrimination ordinances, which has raised the ire of more conservative state houses. Several states have adopted laws related to religious freedom. Utah recently passed a bill aiming to protect people who are LGBT from employment and housing decisions based on their gender identity or sexual orientation, while still protecting religious institutions that oppose homosexuality. The bill did not deal with whether a business can deny services because of religious convictions.

In debating the measure Monday, lawmakers on both sides of the issue cited the Bible to defend their positions, the Indianapolis Star reports.

Republican Rep. Bruce Borders spoke about an anesthesiologist who declined to anesthetize a woman in preparation for an abortion. According to the Star, Borders said he believes the Bible’s command to “do all things as unto the Lord” means religious believers need to be protected not just in church but in their workplaces as well.

Democratic Rep. Ed DeLaney argued that Jesus served all people.

“My prophet had dinner with hookers,” he said, according to The Star. “Was he blessing them? I hope so.”

What this means, in the proverbial simplistic nutshell, is that businesses can pretty much say if their “Deep and Sincerely Held Religious Beliefs” demand it they can discriminate at will. This isn’t a new thing, many states have tried to push similar laws into effect and for 22 years the United States has acted under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and until very recently most people had no idea what the hell that was.

Religious Freedom Restoration Act

Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993

Great Seal of the United States

Long title An Act to protect the free exercise of religion.

Acronyms (colloquial) RFRA

Enacted by the 103rd United States Congress

Effective November 16, 1993

Citations

Public Law 103-141

Statutes at Large 107 Stat. 1488

Codification

Titles amended 42 U.S.C.: Public Health and Social Welfare

U.S.C. sections created 42 U.S.C. ch. 21B § 2000bb et seq.

Legislative history

Introduced in the House as H.R. 1308 by Chuck Schumer (D-NY) on March 11, 1993

Committee consideration by House Judiciary, Senate Judiciary

Passed the House on May 11, 1993 (passed voice vote)

Passed the Senate on October 27, 1993 (97-3, Roll call vote 331, via Senate.gov, in lieu of S. 578) with amendment

House agreed to Senate amendment on November 3, 1993 (without objection)

Signed into law by President William J. Clinton on November 16, 1993

United States Supreme Court cases

City of Boerne v. Flores

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby

v t e

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-141, 107 Stat. 1488 (November 16, 1993), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb through 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb-4 (also known as RFRA), is a 1993 United States federal law aimed at preventing laws that substantially burden a person's free exercise of religion. The bill was introduced by Congressman Chuck Schumer (D-NY) on March 11, 1993 and passed by a unanimous U.S. House and a near unanimous U.S. Senate with three dissenting votes and was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. It was held unconstitutional as applied to the states in the City of Boerne v. Flores decision in 1997, which ruled that the RFRA is not a proper exercise of Congress's enforcement power. However, it continues to be applied to the federal government - for instance, in Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal - because Congress has broad authority to carve out exemptions from federal laws and regulations that it itself has authorized. In response to City of Boerne v. Flores, some individual states passed State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts that apply to state governments and local municipalities.

This law reinstated the Sherbert Test, which was set forth by Sherbert v. Verner, and Wisconsin v. Yoder, mandating that strict scrutiny be used when determining whether the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, guaranteeing religious freedom, has been violated. In the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, Congress states in its findings that a religiously neutral law can burden a religion just as much as one that was intended to interfere with religion; therefore the Act states that the “Government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability.” The law provided an exception if two conditions are both met. First, the burden must be necessary for the “furtherance of a compelling government interest.” Under strict scrutiny, a government interest is compelling when it is more than routine and does more than simply improve government efficiency. A compelling interest relates directly with core constitutional issues. The second condition is that the rule must be the least restrictive way in which to further the government interest. The law, in conjunction with President Bill Clinton's Executive Order in 1996, provided more security for sacred sites for Native American religious rites.

Background and passage

See also: American Indian Religious Freedom Act and Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

This tipi is used for Peyote ceremonies in the Native American Church, one of the main religions affected by the Religious Freedom Restoration Act

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act applies to all religions, but is most pertinent[dubious – discuss] to Native American religions that are burdened by increasing expansion of government projects onto sacred land. In Native American religion the land they worship on is very important. Often the particular ceremonies can only take place in certain locations because these locations have special significance. This, along with peyote use are the main parts of Native American religions that are often left unprotected.

The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment states that Congress shall not pass laws prohibiting the free exercise of religion. In the 1960s, the Supreme Court interpreted this as banning laws that burdened a person's exercise of religion (e.g. Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963); Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972)). But in the 1980s the Court began to allow legislation that incidentally prohibited religiously mandatory activities as long as the ban was "generally applicable" to all citizens. Also, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, intended to protect the freedoms of tribal religions, was lacking enforcement. This led to the key cases leading up to the RFRA, which were Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association (1988) and Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990). In Lyng, the Court was unfavorable to sacred land rights. Members of the Yurok, Tolowa and Karok tribes tried to use the First Amendment to prevent a road from being built by the U.S. Forest Service through sacred land. The land that the road would go through consisted of gathering sites for natural resources used in ceremonies and praying sites. The Supreme Court ruled that this was not an adequate legal burden because the government was not coercing or punishing them for their religious beliefs. In Smith the Court upheld the state of Oregon's refusal to give unemployment benefits to two Native Americans fired from their jobs at a rehab clinic after testing positive for mescaline, the main psychoactive compound in the peyote cactus, which they used in a religious ceremony. Peyote use has been a common practice in Native American tribes for centuries. It was integrated with Christianity into what is now known as the Native American Church.

The Smith decision outraged the public. Many groups came together. Both liberal (like the American Civil Liberties Union) and conservative groups (like the Traditional Values Coalition) as well as other groups such as the Christian Legal Society, the American Jewish Congress, the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, and the National Association of Evangelicals joined forces to support RFRA, which would reinstate the Sherbert Test, overturning laws if they burden a religion. The act, which was Congress's reaction to the Lyng and Smith cases, passed the House unanimously and the Senate 97 to 3 and was signed into law by U.S. President Bill Clinton.

Applicability

The RFRA applies "to all Federal law, and the implementation of that law, whether statutory or otherwise", including any Federal statutory law adopted after the RFRA's date of signing "unless such law explicitly excludes such application."[9]

Challenges and weaknesses

The Peyote cactus, the source of the peyote used by Native Americans in religious ceremonies.

In 1997, part of this act was overturned by the United States Supreme Court. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Antonio wanted to enlarge a church in Boerne, Texas. But a Boerne ordinance protected the building as a historic landmark and did not permit it to be torn down. The church sued, citing RFRA, and in the resulting case, City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997), the Supreme Court struck down the RFRA with respect to its applicability to States (but not Federally), stating that Congress had stepped beyond their power of enforcement provided in the Fourteenth Amendment. In response to the Boerne ruling, Congress passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) in 2000, which grants special privileges to religious land owners.

The Act was amended in 2003 to only include the federal government and its entities, such as Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. A number of states have passed state RFRAs, applying the rule to the laws of their own state, but the Smith case remains the authority in these matters in many states.

The constitutionality of RFRA as applied to the federal government was confirmed on February 21, 2006, as the Supreme Court ruled against the government in Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418 (2006), which involved the use of an otherwise illegal substance in a religious ceremony, stating that the federal government must show a compelling state interest in restricting religious conduct.

Post-Smith, many members of the Native American Church still had issues using peyote in their ceremonies. This led to the Religious Freedom Act Amendments in 1994, which state, "the use, possession, or transportation of peyote by an Indian for bona fide traditional ceremony purposes in connection with the practice of a traditional Indian religion is lawful, and shall not be prohibited by the United States or any state. No Indian shall be penalized or discriminated against on the basis of such use, possession or transportation."

Applications and effects

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act holds the federal government responsible for accepting additional obligations to protect religious exercise. In O'Bryan v. Bureau of Prisons it was found that the RFRA governs the actions of federal officers and agencies and that the RFRA can be applied to "internal operations of the federal government."

As of 1996, the year before the RFRA was found unconstitutional as applied to states, 337 cases had cited RFRA in its three year time range. It was also found that Jewish, Muslim, and Native American religions, which make up only three percent of religious membership in the U.S., make up 18 percent of the cases involving the free exercise of religion. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act was a cornerstone for tribes challenging the National Forest Service’s plans to permit upgrades to Snow Bowl Ski Resort. Six tribes were involved, including the Navajo, Hopi, Havasupai, and Hualapai. The tribes objected on religious grounds to the plans to use reclaimed water. They felt that this risked infecting the tribal members with “ghost sickness” as the water would be from mortuaries and hospitals. They also felt that the reclaimed water would contaminate the plant life used in ceremonies. In August 2008, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected their RFRA claim.

In the case of Adams v. Commissioner, the United States Tax Court rejected the argument of Priscilla M. Lippincott Adams, who was a devout Quaker. She tried to argue that under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, she was exempt from federal income taxes. The U.S. Tax Court rejected her argument and ruled that she was not exempt. The Court stated: "...while petitioner's religious beliefs are substantially burdened by payment of taxes that fund military expenditures, the Supreme Court has established that uniform, mandatory participation in the Federal income tax system, irrespective of religious belief, is a compelling governmental interest." In the case of Miller v. Commissioner, the taxpayers objected to the use of social security numbers, arguing that such numbers related to the "mark of the beast" from the Bible. In its decision, the U.S. Court discussed the applicability of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, but ruled against the taxpayers.

The RFRA figured prominently in oral arguments in the case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, heard by the Supreme Court on March 25, 2014. In a 5-4 decision, Justice Alito stated, that the RFRA did not just restore the law as before Smith but contains a new regulation that allows to opt out of federal law based on religious beliefs.

Now before you say some asinine version of;

“Well Josh, that will be knocked down as unconstitutional so just calm down and stop making me feel uncomfortable for kinda wanting this to be a thing because the gays make me feel icky and wrong.”

Or,

“It’s my right as a Murikan to deny service to whoever I want even though that used to be the law and it ended up in near revolution and with a lot of colored folks hanging from trees and a church filled with little dead black kids (amongst thousands of other terroristic crimes). Also I don’t care that public businesses benefit from the infrastructure and services my taxes support either because queers, fags, dykes (at least the ugly ones), spikes, niggers, gooks, rag heads, and anyone else not white enough for me are the enemy!!!”

Please allow me to tell you to go fuck yourself, never buy any of my books, and delete yourself any social media site we are “Friends” on. I want nothing more to do with you and we’d be better off forgetting that one another coexist on the same level of the Tower.

Are we 100% clear?

Good, moving on.

One of the reasons this has stuck so firmly in my craw, besides the obvious moral reasons, is because I go to Indiana every year. We, as a family, allow ourselves one no debate vacation every year. We attend Gen Con in Indianapolis faithfully, it’s the tent pole of our year and other than Christmas the thing I look forward to the most, and some of the best memories I have with my kids in the last few years took place there.

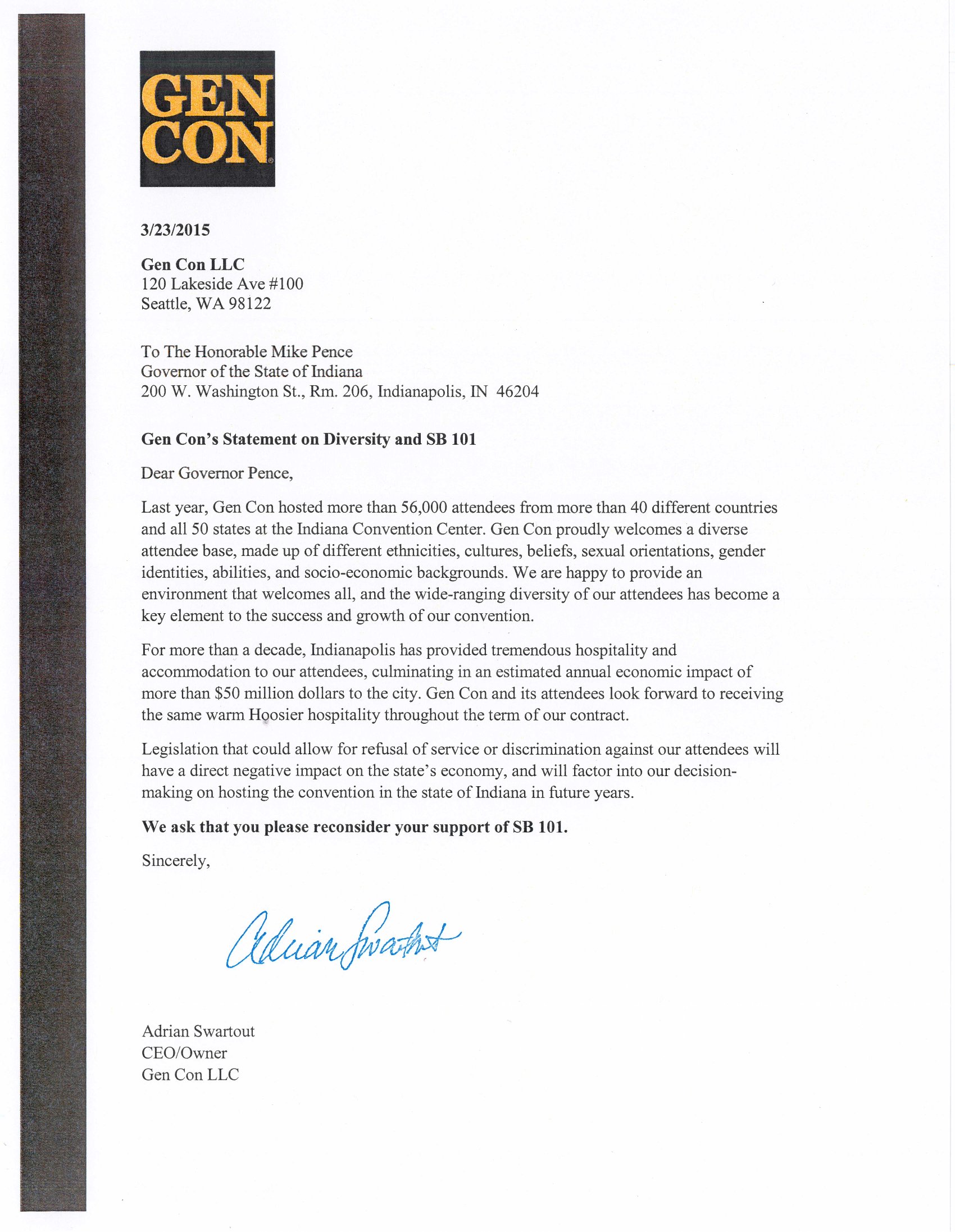

I wondered how Gen Con would react to the inevitable passage of SB101. Here’s a sample of their reply (click the link below to read the entire Gen Con letter to Governor Mike Pence).

“Last year, Gen Con hosted more than 56,000 attendees from more than 40 different countries and all 50 states," Swartout wrote to the governor. "Gen Con proudly welcomes a diverse attendee base, made up of different ethnicities, cultures, beliefs, sexual orientations, gender identities, abilities, and socio-economic backgrounds. We are happy to provide an environment that welcomes all, and the wide-ranging diversity of our attendees has become a key element to the success and growth of our convention.

"Legislation that could allow for refusal of service or discrimination against our attendees will have a direct negative impact on the state's economy."

CLICK HERE TO READ THE GEN CON RESPONSE

Right now the gamer community is in the process of shitting their collective pants. For the most part gamers and industry members have taken a stance in line with Gen Con. This didn’t surprise me, if I’ve learned one thing about gamers we tend to be a relatively inclusive lot of misfits and malcontent geeks, what did surprise me was the pushback.

I was shocked to see how many gamers, some of them I know personally, who have an issue with this. Please know even though I don’t want to name them I’m not talking about friends I sometime debate issues of politics with if I debate with you we’re cool. I’m not talking about people with different opinions having a discussion I’m talking about a significant segment of the community that seems more or less okay with legal discrimination.

I’m more than a little taken aback.

Do I think this will all eventually be overturned and relegated to the trash heap of history with “Coloreds Only” signs?

Yes, yes I do. But I think what we need is more people making a stink. We need people to get on their real and metaphorical rooftops to shout down the hate and discrimination. We need to keep owning this fight because I demand my children have the right to bring their children into a better world.

- Josh